Material Opportunities: Concrete

As a break from my theme of the architect’s role in the project delivery process I will be starting this miniseries of blog posts entitled “material opportunities”. I will be using this to delve a little deeper into the materials and processes I am studying. First on the docket is concrete.

Every time we were assigned a new project in studio course someone would inevitably decide to experiment with concrete. I’ll admit, it does have many impressive material qualities, but its use is not without its challenges.

To me the most interesting aspect of concrete isn’t the material itself but rather the inverse- the processes and materials that are used to turn a liquid into the world’s most ubiquitous building material. More specifically, I think it could be argued that formwork construction is the most challenging and impressive aspect of this seemingly magical material.

In reading more on the subject I came across an essay called “A Building and Its Double” by Mabel Wilson. This essay describes the sculpture ‘House’ by Rachel Whiteread in London. In this project Whiteread cast the inside of a Victorian house in concrete.

This project brings a visual aspect to an idea that we touched on in class- the idea that a concrete building is really “built” three times. Once in the formwork, once in the reinforcement, and finally, in the concrete.

Being that it is clearly critical to the final result I decided to look more into the opportunities, and challenges, presented in formwork construction.

In his book ‘Stuff Matters’ Mark Middownik says “If you can build the mold [formwork] you can create the structure.” After that all you need is some steel, cement, aggregate, and water and you’ve got your concrete building. However, it’s not quite that easy, or simple.

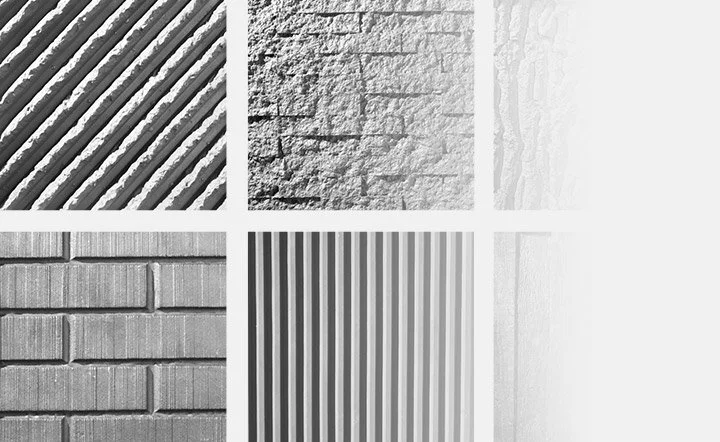

To achieve the aesthetic qualities specified by the architect, builders must come up with inventive ways to create functional formwork. Since formwork construction is considered means and methods, it is up to the contractor to design and build. Below I have given some examples of the different formwork types and materials that are being used to achieve these architectural goals. A quick note, this type of concrete construction is considered “architectural concrete” meaning that it has a visible finish surface. This distinguishes it from structural concrete such as floor slabs and hidden columns, etc. Structural concrete can have some inventiveness with its formwork, but there are more prescribed, traditional methods to form those portions of the building.

All of these styles of formed concrete are generally grouped under the heading (and specification section) of ‘Architectural Concrete’. While I haven’t had the opportunity (yet) to utilize these decorative styles of concrete in any of my built work, I believe the opportunities for it’s use, even in residential work are incredibly interesting. One thing I do find disheartening in researching these methods, and the projects utilizing them, is that the builder is almost never given credit in the articles describing them in architectural journals and websites. I find it unethical on the part of the architecture industry not to give more credit to the builders for making their drawings into reality, they did not achieve these results on their own.

Originally published October 26, 2018 (edited)